So, with the release of a brand new Toho-produced Godzilla film in Godzilla: Minus One I felt there was no better time to dive back into the world of Godzilla cinema. The next film in the series up for a review retrospective is 1964’s Mothra vs. Godzilla, also known as Godzilla vs. The Thing. But Godzilla isn’t the only movie monster Toho holds the rights to. Before we move into Mothra vs. Godzilla we are taking a look at the debut film of everyone’s favorite movie moth, this is 1961’s Mothra!

Introduction & Pre-Release

When many people think of Toho, Godzilla is likely the first thing that comes to mind. But in actuality Toho has produced a number of different films starring different monsters. They may not have had the same mass appeal as the king of the monsters, but they are still an important part of Toho’s filmography. Mothra herself has gone on to become Toho’s second most popular movie monster after the G-man Godzilla and would become a mainstay within Godzilla’s filmography over the years. Often represented as a more heroic righteous monster especially when compared to Godzilla, the symbol of atomic horrors and annihilation.

Several of Toho’s movie monsters often found themselves trapped as secondary characters within the Godzilla universe, but Mothra was one of the exceptions that had a debut film, but rarer than that, she had her film series, namely the Rebirth of Mothra trilogy in the 1990’s. The story of Mothra’s production begins in 1960 when film producer Tomoyuki Tanaka hired writer Shin’ichiro Nakamura to pen a script for a new monster film. The story was co-written by Nakamura, Takeihiko Fukunaga and Yoshie Hotta.

The story was initially serialized in a magazine titled as The Glowing Fairies and Mothra in January of 1961. The story was later adapted to a film screenplay by screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa, who took some inspiration from RKO’s King Kong (1933) and Godzilla (1954). The film was directed by the legendary Ishiro Honda, the director and mind behind the original Godzilla film. The film starred Frankie Sakai, Hiroshi Koizumi, and Kyoko Kagawa. The film’s cinematography was handled by Hajime Koizumi, whilst the music was composed by Yuji Koseki. The film initially released in Japan on July 30, 1961 and saw a western theatrical release in May of 1962 through Columbia Pictures.

Synopsis & Writing

Somewhere off the coast of Japan a survey team comes across the remote Infant Island where local tribes worship a pair of small fairies and the guardian of the island, a mysterious beast known only by the name of Mothra. However when a corrupt businessman from the Japanese mainland abducts the fairies in an attempt to make a quick yen or buck off of this newly discovered wonder, he unknowingly unleashes Mothra’s wrath on an unprepared Japan.

Like many monster movies of the era Mothra presents a very simple setup that you have more than likely seen before. However, much like the thematically loaded films of Honda’s past he interweaves many deeper themes and subtexts across the narrative. In comparison to Mothra’s reptilian predecessor Godzilla, Mothra is represented as a more sympathetic creature. In all of her appearances across the decades Mothra is represented as a benevolent creature who only becomes an active force to protect her fairies, and more often the earth. She is a symbol of guardianship and tranquility compared to Godzilla’s more retribution-prone hostile nature.

Having seen the likes of Mothra vs. Godzilla before, I was initially surprised by how much inspiration Toho had drawn from this film, as they aren’t one-to-one copies or rip offs of one another. But the inspiration was clear and obvious within the script writing and themes presented. And would you believe it; Honda was the director for both films.

And much like Godzilla 1954 Honda loaded this film with his classic political satire. Within the story we are introduced to the fictional country of “Roliscia,” an amalgam of Russia and America. Rolisicia is represented as a pushy capitalist superpower that initially refuses to get involved in Japan’s plight as they feel there is no link between the abduction of 12-inch fairy girls and the sudden attack of a giant radioactive moth. And Rolisicia only intervenes when the assets of said abducting businessman are seized. Like many other monster movies of the era there is fairly noticeable commentary of nuclear arms and their use. Honda’s political satire is usually meant in good fun and mainly serves as food for thought.

Mothra is rather unique among monster movies of the era in that she may be actively bringing destruction to Japan but she is presented more as a protagonist and not a full-on villain or force of destruction like Godzilla was presented to be. The film’s antagonist is obviously presented to be decidedly human. Humans being the real monsters may lack subtlety, but I imagine many aren’t watching a kaiju movie for subtlety.

Regardless of which version you’re watching Mothra is a film that places great responsibility upon its characters as Mothra herself doesn’t appear until at least 45 minutes in, meaning for better or worse the majority of the film’s runtime is spent with your human cast. The film does a marvelous job of giving Mothra the reverence she deserves as a mythical-like being. Despite not being constantly on screen Mothra’s presence is constantly felt and when she finally arrives on screen she is given the grandeur she deserves

Presentation & Score

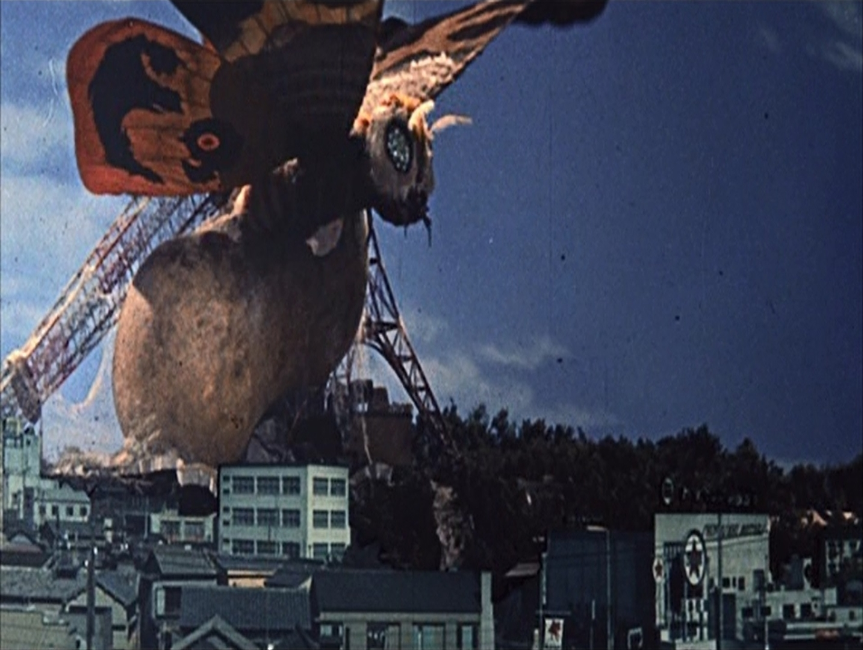

The special effects for any Toho film are often an involved process especially at this point in time where practical effects were commonplace. This goes beyond creating miniature buildings to be shot at from various angles to keep the effect of scale. The film’s special effects were created and coordinated by Eiji Tsuburaya who not only created miniature buildings but also various water tanks and dams to burst in a particular scene. The dam was built at 1/50th scale and over 12 tanks of water consisting of 4,320 gallons in total were used in order to create an authentic scene of a dam rupturing.

Mothra’s caterpillar form is actually several actors within a sizable suit. It was the largest monster suit Toho had produced at the time at a length of seven meters. Six people fit inside the suit and moved in unison to create the movements as we see them in the film. There was also a hand operated model of larva Mothra for distance shots. Adult Mothra, however, was brought to life by no less than three different models each with different functions. The scene in which adult Mothra hatches involved using an exclusive mid-sized model with flexible wings. All of Adult Mothra’s movements were perpetrated by wires used to suspend and move the various models. Toho hides them very well through creative angles, but despite this Mothra’s movements feel very organic and fluid, not at all like a puppet on a string.

The climax of the film takes place in a city setting, but Toho expressed that they desired a more budget friendly setting for a climax. This alternate ending would have had our villain cast into an active volcano, so they filmed this alternate cut of the ending on location at Mount Kirishima, however Columbia Pictures denied this, saying that the climax needed to be filmed in a location that could pass for an American city, which fell in line with Honda’s original vision for the film. But its also interesting in the sense that Toho allowed an American based company to make a critical decision regarding the production of a Japanese film. It makes some sense as finding a new production company to partner with for a western release would have cost Toho a significant amount. So, in the end it was easier to go along with their desires, and it just so happened to be what the writer and director of the film wanted.

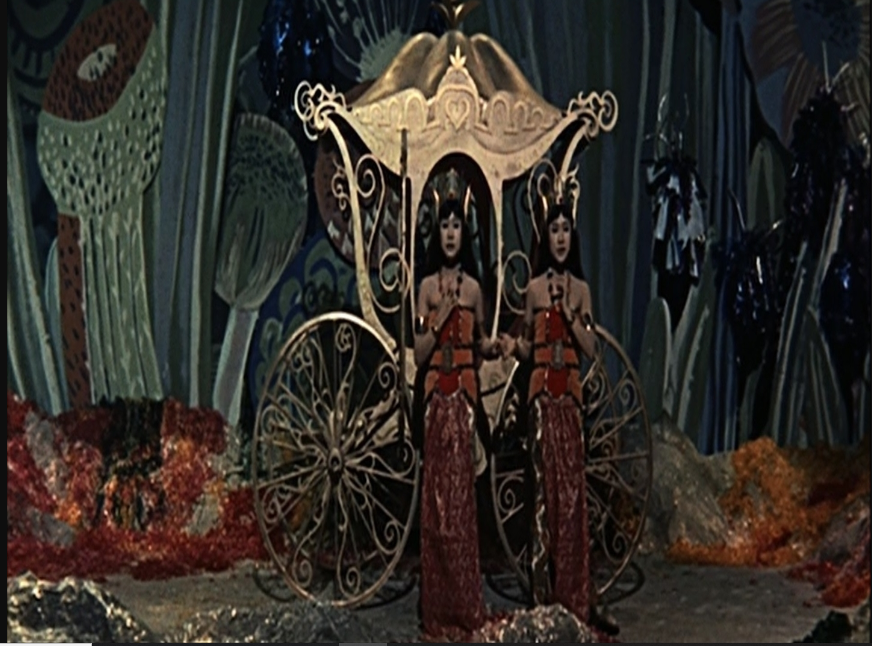

Originally, the score was offered to longtime Godzilla composer Akira Ifukube, but he declined as he didn’t feel confident enough to create music for the Japanese music duo Toho had cast as the fairies Emi and Yumi Ito. Better known as the “Peanuts,” instead we have Yuji Koseki taking up composition. The lyrics for the Mothra theme were written in Japanese initially and translated into Indonesian by an exchange student at Tokyo University. When the film was released for home purchase, several tracks of the score were missing such as “The Girls of Infant Island” and “Song of Mothra,” so they wouldn’t see release for public purchase until 1961 and 1978 respectively. The Song of Mothra would go on to be a pop culture reference in Japan all the way through the 1990s as a song that those who hadn’t even seen the movie were aware of. This was partially due to its presence alongside a Mothra cameo on Cheers, Mr. Awamori.

Conclusion

What began as an independent monster film has gone on to become an unforgettable part of Toho’s monster library. Despite only releasing four films of her own, Mothra as a character and an icon has maintained a presence in people’s memory. Mothra is a strong kaiju film, in its era as well as today. I recommend it to all fans of monster movies and look forward to seeing her next week when we cover Mothra vs. Godzilla.

Patron Shout-Out

Special thanks to our patrons without the support of whom our work would not be possible: Francesco Santoyo